Utilitarians Should Accept that Some Suffering Cannot be “Offset”

Note: see further discussion on the EA Forum

What follows is the result of my trying to reconcile various beliefs and intuitions I have about the nature of morality, namely why arguments for total utilitarianism seemed so compelling on their own and yet some of the implications seemed not merely weird but morally implausible.

Intro

This post challenges the common assumption that total utilitarianism entails offsetability,1 or that any instance of suffering can, in principle, be offset by sufficient happiness. I make two distinct claims:

Logical: offsetability does not follow from the five standard premises that constitute total utilitarianism (consequentialism, welfarism, impartiality, summation, and maximization). Instead, it requires an additional, substantive, plausibly false premise.

Metaphysical: some suffering in fact cannot be morally justified (“offset”) by any amount of happiness.

While related, the former, weaker claim stands independently of the latter, stronger one.

How to read this post

Different readers will find different parts most relevant to their concerns:

If you believe the math or logic of utilitarianism inherently requires offsetability (that is, if you think “once we accept utilitarian premises, we’re logically committed to accepting that torture could be justified by enough happiness”), start with Part I. There I show why this common assumption is mistaken.

If you’re primarily interested in whether extreme suffering can actually be offset (that is, if you already see offsetability as an open philosophical question rather than a logical necessity), you may wish to skip directly to Part II, where I argue the more substantive metaphysical claim.

Part I: The logical claim

Offsetability doesn’t fall out of the math

A brief aside

I’ve found that two relatively distinct groups tend to be interested in part I:

The philosophy-brained, who have taken the implicit “representation premise” I discuss below as a given and are primarily interested in conceptual arguments.

The math-brained, for whom alternatives to the “representation premise” are obviously on the table and who are primarily interested in rigorous formalization of my claim.

If it ever feels like I’m equivocating - perhaps becoming too lax in one sentence and excessively formal in the next, you’d be right! Sorry. I have tried to put much of the formalization in footnotes, so the math-brained should be encouraged to check those out, but the post isn’t really optimized for either group.

1. Introduction: what we take for granted

The standard narrative about total utilitarianism goes something like: “once we accept that rightness depends on consequences, that (for the purpose of this post, hedonic) welfare is what matters, that we should sum welfare impartially across individuals, and that more welfare is better than less, it follows naturally that everything becomes commensurable.

And, more specifically, I mean “commensurable” in the sense that all goods and bads fundamentally behave like numbers in the relevant moral calculus: perhaps 15 for a nice day on the beach, -2 for a papercut, and so on.23 If so, it would seem to follow that any instance of suffering can, in principle, be offset by sufficient happiness, and obviously so.

I think this is false.

2. The meaning of utilitarianism and the hidden sixth premise

My primary intention here is not to make an argument about how words should be used, but rather to make a more substantive claim about what implications follow from certain premises.

Here I describe what I mean when I talk about total utilitarianism.

The Utilitarian Core

To the best of my understanding, total utilitarianism is constituted by five necessary and sufficient consensus premises and propositions,4,which I’ll call the Utilitarian Core, or UC:5[5]

Consequentialism: the rightness of actions depends on their consequences (as opposed to, perhaps, the nature of the acts themselves or adherence to rules).

[Hedonic] welfarism: the only thing that matters morally is the hedonic welfare of sentient beings. Nothing else has intrinsic moral value.

Impartiality: wellbeing matters the same regardless of whose it is, with no special weight for kin relationships, race, gender, species, or other arbitrary characteristics.

Aggregation or summation: the overall value of a state of affairs is determined by aggregating or summing individual wellbeing.6

Maximization: the best world is the one with maximum aggregate wellbeing.

What is left out

The UC tells us to maximize the sum of welfare, but remains silent on what exactly is getting summed.

You can’t literally add up welfare like apples (i.e., by putting them in a literal or metaphorical basket). In some important sense, then, “summation” or “aggregation” refers to the claim that the moral state of the world simply is the grouping of the moral states that exist within. How exactly to operationalize this via some sort of conceptual/ideal or literal/physical process or model is entirely non-obvious.7

Representation premise.

To get universal offsetability, you need more structure than the Utilitarian Core provides. A sufficient additional assumption, if you want offsetability by construction, is to assume that welfare sits on a single number line where we can add people’s contributions, where every bad has a positive opposite, and where there are no lexical walls that a large enough amount of good could not overcome.

In practice, I think, this generally looks like an assumption that all states of hedonic welfare are adequately modeled by the real numbers with standard arithmetic operations.8

The Core itself does not force that choice. At most it motivates a way to combine people’s welfare that is symmetric across persons and monotone in each person’s welfare. If you drop either the “no lexical walls” condition or the “every bad has a positive opposite” condition, offsetability can fail even though you still compare and aggregate.9

Without this additional premise (i.e. of some additional structure such as the one described above), the standard utilitarian framework doesn’t entail that any amount of suffering can be offset by sufficient happiness.

The crucial point is that the Representation Premise is not a logical consequence of the Utilitarian Core. It is a substantive and plausibly false metaphysical claim about the nature of suffering and happiness that typically gets smuggled in without justification.

3. Why real-number representation isn’t obvious

What utilitarianism actually requires

The five core premises of utilitarianism establish the need for comparison and aggregation, but they don’t imply the existence of cardinal units that behave like real numbers. We need only be able to say “this outcome is better than that one” and to sum representations of individual welfare into a representation of social welfare.

One intuitive and a priori plausible operationalization is that any hedonic event corresponds naturally to a real number that accurately represents its moral value. But “a priori plausible” doesn’t mean “true,” and indeed the UC does not require this.

Where cardinality might hold (and where it might not)

To be clear, there are good arguments for partial cardinality in welfare. Setting aside whether they’re logically implied by UC, I (tentatively) believe that, in a deep and meaningful sense, subjective duration of experience and numbers of relevantly similar persons are cardinally meaningful in utilitarian calculus.10

That is, suffering twice for what feels like as long really is twice as bad. Fifty people enjoying a massage is exactly 25% better than forty people doing so. In general, conditioning on some specific hedonic state, person-years (at least when both figures are finite)11 really do have properties we associate with real numbers: they are Archimedean, follow normal rules of arithmetic, and so on.

But this limited cardinality for duration and population doesn’t establish that all welfare comparisons map to real numbers. The intensity and qualitative character of different experiences might not admit of the same mathematical treatment. The assumption that they do (e.g., that we can meaningfully say torture is 1,000 or 1,000,000 times worse than a pinprick) is precisely what needs justification.

Alternative mathematical structures

Many mathematical structures preserve the ordering and aggregation that utilitarianism requires without implying universal offsetability:

Lexicographically ordered vectors (R^n with dictionary ordering12) might be the most natural alternative. Here, welfare could have multiple dimensions ordered by priority: catastrophic suffering first, then all forms of wellbeing and lesser suffering. Or perhaps catastrophic suffering, then lexical happiness (“divine bliss”) then ordinary hedonic states, or any number of “levels” to lexical suffering. This preserves all utilitarian operations while rejecting offsetability between levels.13

Hyperreal numbers

The hyperreal system extends the reals with infinitesimal and unlimited magnitudes. You can map catastrophic suffering to a negative non-finite value, call it −H_unlimited , and ordinary goods to finite values. Then −H_unlimited+1000 is better than −H_unlimited , so extra happiness still matters, but no finite increase offsets −H_unlimited. This blocks offsetability while preserving familiar arithmetic.14 15

The point

I introduce these alternatives not to argue here that any particular mathematical structure is correct, but to illustrate something deeper: there is no special “math” constraint above and beyond what the real world permits.

Mathematicians have every right to invent arbitrary exotic, internally consistent systems built on top of their choice of axioms and investigate what follows. But when using math to model reality, axioms are substantive claims about what you think the world is like.

This matters because in other domains, reality often diverges from our mathematical intuitions. Quantum mechanics requires complex numbers, not just reals. Spacetime intervals don’t add linearly but combine through curved geometry. The assumption that consciousness and welfare fit neatly on the real number line is a reasonable hypothesis but simply not an obvious truth.

Perhaps welfare really does map to real numbers with all that entails. Further investigation or compelling philosophical argument may establish this. But, as I wrote in my original post on this matter, “if God descends tomorrow to reveal that [all hedonic states correspond to real numbers], we would all be learning something new.”16

Again, the mathematical framework is just the toolbox. Whether actual experiences can ever map to infinite values within that framework is the separate quasi-empirical and philosophical question that the rest of this post addresses.

4. The VNM (non-) problem

Defenders of offsetability sometimes invoke the Von Neumann-Morgenstern theorem (“VNM”), alleging that VNM proves that rational preferences can be represented by real-valued utility functions. However, this does not hold in our case because non-offsetability implies a rejection of continuity, one of the four conditions required by the theorem to hold.

I admit this is an extremely understandable error to make in part because I myself was confused and frankly wrong about the theorem when I first encountered it as an objection. In a reply to me a few years ago, friend and prolific utilitarian blogger Matthew Adelstein (@Bentham’s Bulldog) wrote that:

Well, the vnm formula shows one’s preferences will be modelable as a [real-valued] utility function if they meet a few basic axioms

To which I made the following incorrect response:

VNM shows that preferences have to be modeled by an *ordinal* utility function. You write that…’Let’s say a papercut is -n and torture is -2 billion.’ but this only shows that the torture is worse than the papercut - not that it is any particular amount worse. Afaik there’s no argument or proof that one state of the world represented by (ordinal) utility u_1 is necessarily some finite number of times better or worse than some other state of the world represented by u_2

My first sentence, “VNM shows that preferences have to be modeled by an *ordinal* utility function,” was totally incorrect. VNM does result in cardinally meaningful utility that respects standard expected value theory, but only conditional on four specific axioms or premises:17

Completeness: option A is better than option B (A ≻ B) or are of equal moral value (A ~ B)

Transitivity: If A ≻ B and B ≻ C, then A ≻ C

Continuity: If A ≻ B ≻ C, there’s some probability p ∈ (0, 1) where a guaranteed state of the world B is ex ante morally equivalent to “lottery p·A + (1-p)·C” (i.e., p chance of state of the world A, and the rest of the probability mass of C)

Independence: A ≻ B if and only if [p·A + (1-p)·C] ≻ [p·B + (1-p)·C] for any state of the world C and p∈(0,1) (i.e., adding the same chance of the same thing to all world states doesn’t affect their moral ordering)

The theorem states that if these four conditions hold then there exists a real valued utility function u that respects expected value theory18, which implies meaningful cardinality and restriction to the set of real numbers, which in turn implies offsetability.19

Quite simply, VNM does not apply in the context of my argument because I reject premise 3, continuity. And, in more general terms, it is not implied by UC.

More specifically, I claim that there exists no nonzero probability p such that a p chance of some extraordinarily bad outcome (namely, catastrophic suffering) and a (1-p) chance of a good world is morally equivalent to some mediocre alternative. In other words, the value of a state of the world (which includes probability distributions over the future) becomes radically different as you change from “very small possibility” of some catastrophic suffering in the future to “zero.”

To be clear, I haven’t really argued for that conclusion on the merits yet and reasonable people disagree about this. I will, in section II. The point here is just that UC does not entail the conditions necessary to imply meaningful cardinality via VNM, at the very least because of the counterexample described just above.

Not an epistemic “red flag”

It’s worth noting that assuming the relevant assumptions such that VNM holds is often a good guess. Two of the axioms are essentially entailed by what most people mean by “rationality,” three seem on extremely good footing, and all four are decidedly plausible.20

But rejecting premise 3, continuity, is perfectly coherent and doesn’t create the problems often associated with “irrational” preferences. An agent with lexical preferences (i.e., and e.g., who refuses any gamble involving torture no matter what the potential upside) violates continuity but remains completely coherent and consistent; there are no Dutch books (you can’t construct a series of trades that leaves them strictly worse off) or money pumps (you can’t exploit them through repeated transactions). They maintain transitivity and completeness.

Part II: The metaphysical claim

Some suffering actually can’t be offset

I now turn to the stronger claim that some suffering actually cannot be offset by any amount of happiness.

5. The argument from idealized rational preferences

The setup: you are everyone

Imagine that you become an Idealized Hedonic Egoist (IHE). In this state, you are maximally rational:21 you make no logical errors, have unlimited information processing capacity, complete information about experiences with perfect introspective access, and full understanding of what any hedonic state would actually feel like. You care only about your own pleasure and suffering in exact proportion to their hedonic significance.

Now imagine that as this idealized version of yourself, you will experience everyone’s life in a given outcome. Under this “experiential totalization” (ET), you live through all the suffering and all the happiness that would exist. For a hedonic total utilitarian, this creates a perfect identity: your self-interested calculation becomes the moral calculation. What’s best for you-who-experiences-everyone is precisely what utilitarianism says is morally best.

The question

As this idealized being who will experience everything, you face a choice: Would you accept 70 years of the worst conceivable torture in exchange for any amount of happiness afterward?

Take a moment to really consider what “worst conceivable torture” means. Our brains aren’t built for this, but it can reason by analogy: being boiled alive; the terror of your worst nightmare; the horror and existential regret of a mother watching her son fall to his death after reluctantly telling him he could play near the canyon edge; slowly asphyxiating as your oxygen runs out. All mitigating biological relief systems that sometimes give you a hint of meaning or relief even as you suffer would be entirely absent. All of these at once, somehow, and more. For 70 years.

Imagine what follows, as well, by all means: falling in love, peak experiences, the jhanas, drowning in unfathomable bliss, love, awe, glory, interest, excitement, gratitude, connection, and wonder. Not just for 70 years but for millennia, eons, until the heat death of the universe.

As an IHE who will experience all of this, knowing exactly what each part would feel like, do you take this deal?

As a matter of simple descriptive fact, I, Aaron, would not, and I don’t think I would if I was ideally rational either.

I also imagine accepting the deal and later being asked, with all the suffering behind me, “was it worth it?” And I think I would say “no, it was a terrible mistake.”

The burden of idealization

Some readers might think “I wouldn’t personally take this trade, but that’s just bias. The perfectly rational IHE would, so I would too if I became perfectly rational.”

This response deserves scrutiny, particularly if and once you’ve accepted the argument in part I that offsetability is not logically or mathematically inevitable.

To claim the IHE would accept what you’d refuse requires believing that your cognitive biases not only persist in spite of but essentially circumvent and overcome a conceptual setup specifically designed to elicit the epistemic clarity that comes with self-interest and conceptually simple trades on offer.

There is a clear similarity between this thought experiment and the conceptual and empirical use of revealed preference in social science, especially economics.

To argue that the revealed hypothetical preference of this thought experiment is fundamentally wrong or misleading by the standard of abstract rationality and hedonic egoism is not analogous to arguing that a specific empirical context leads consumers to display behavior that diverges from the predictions of some simplified model of rational behavior; it is analogous to arguing that a specific context leads consumers to behave in such a way that is fundamentally contrary to their truest and most ultimate values and preferences. This latter thing is a much stronger claim.

What this reveals

If you share my conviction that you-as-IHE would refuse the torture trade, then you should be deeply suspicious of any moral theory that says creating such trades is not just acceptable but sometimes obligatory. The thought experiment asks you to confront what you actually believe about extreme suffering when you would be the one experiencing all of it. You can’t hide behind aggregate statistics or philosophical abstractions.

Not a proof

I recognize that this thought experiment is merely an intuition pump - directional evidence, not a proof.

I don’t expect to convince all readers, but I’d be largely satisfied if someone reads this and says: “You’re right about the logic, right about the hidden premise, right about the bridge from IHE preferences to moral facts, but I would personally, both in real life and as an IHE, accept literally anything, including a lifetime of being boiled alive, for sufficient happiness afterward.”

This, I claim, should be the real crux of any disagreement.

To explicitly link this to Part I: what the IHE would choose is a fundamental question about the nature of hedonic states. It doesn’t “fall out” of any axioms or mathematical truths. Any mathematical modeling must be built up from interaction with the territory. The IHE thought experiment, I claim, is an especially epistemically productive way of exploring that territory, and indeed for doing moral philosophy more broadly.

6. The implications of universal offsetability are especially implausible

Most utilitarians I know are deeply motivated by preventing and alleviating suffering. They dedicate their time, money, and sometimes entire careers to reducing factory farming and preventing painful diseases.

Yet the theory many of them endorse says something quite different. Universal offsetability doesn’t just permit creating extreme suffering when necessary; it can enthusiastically endorse package deals that contain it.22

If any suffering can be offset by sufficient happiness, then creating a being to be boiled alive for a trillion years is not merely acceptable because all alternatives include more or worse suffering but because it’s part of an all-or-nothing package deal with sufficiently many happy beings along for the ride.

When I present this trade to utilitarian friends and colleagues, many recoil. They search for reasons why this particular trade might be different, why the theory doesn’t really imply what it seems to imply. Some bite the bullet (for what I sense is a belief that such unpalatable conclusions follow from very compelling premises - the thing that part I of this essay directly challenges). Very few genuinely embrace it.

I think their discomfort is correct and their theory is wrong.

The moral difference

There’s a profound difference between these scenarios:

Accepting tragic tradeoffs: Allowing, or even creating, some suffering because it’s the only way to prevent more or more intense suffering

Creating offsetting packages: Actively creating torture chambers because you’ve also created enough pleasure to “balance the books”

The former involves minimizing harm in tragic circumstances. Every moral theory faces these dilemmas. But the second involves creating more extreme suffering than would have otherwise existed, justified solely by also creating positive wellbeing. The theory says that while we might regret the suffering component, the overall package is not just acceptable but optimal. We should prefer a world with both the torture and offsetting happiness to one with neither.

Scale this up and offsetability doesn’t reluctantly permit but instead actively recommends creating billions of beings in agony until the heat death of the universe, as long as we create enough happiness to tip the scales. The suffering isn’t a necessary evil; it’s part of a package deal the theory endorses as an improvement to the world.

When your theory tells you to endorse deals that create vast torture chambers (even while regretting the torture component), the problem isn’t with your intuitions but with the hidden premises that feel from the inside like they’re forcing your hand.

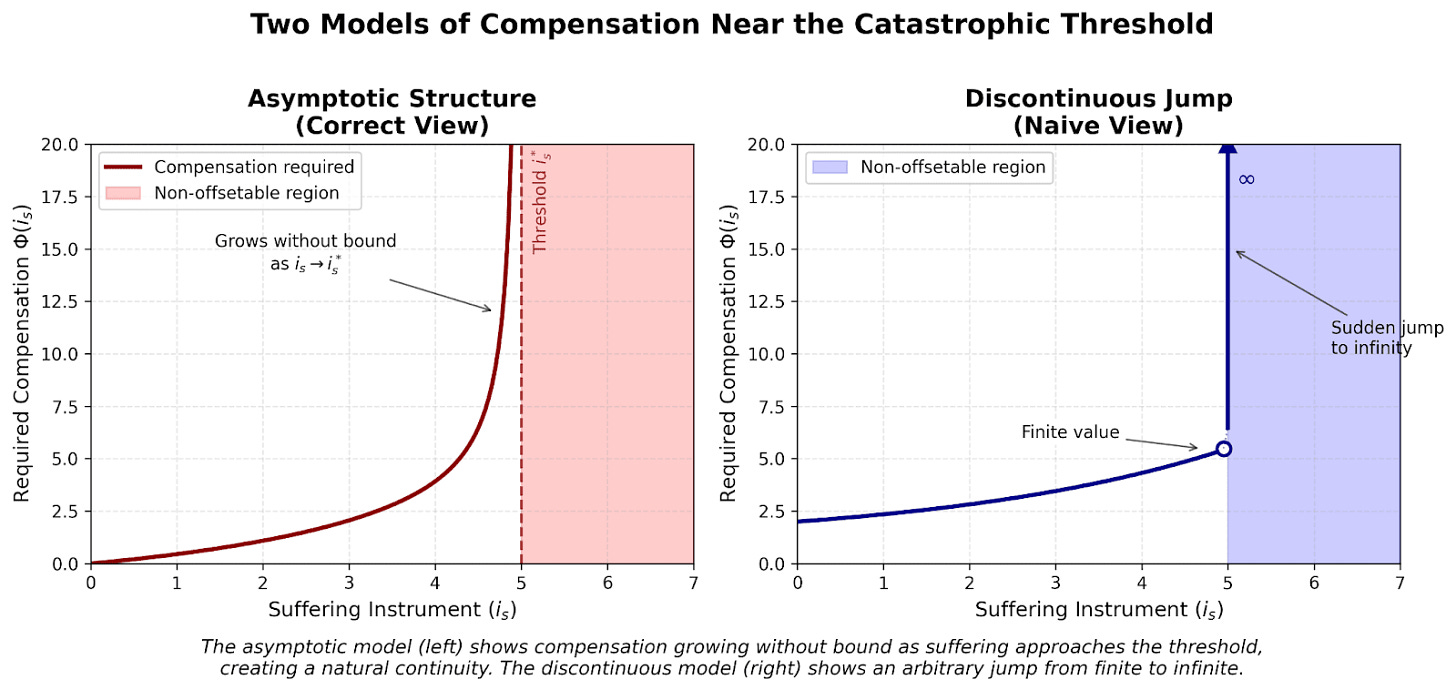

7. The asymptote is the radical part

In this section I offer a conceptual reframing that draws attention away from the severity of suffering warranting genuine conceptual lexicality and towards the suffering that is slightly less severe. I argue that, insofar as my view is radical, the radical part of my view happens before the lexical threshold, in what appears to be the “normal” offsetable range.

To see why, let’s use a helpful conceptual framework

Instruments: measurable proxies that track suffering and happiness.

A suffering instrument (i_s) could be neurons engaged in pain signaling or temperature of an ice bath. A happiness instrument (i_h) might be neurons in reward processing or some measure of endocannabinoid release. For our purposes, these are entirely conceptual devices. These instruments need only be monotonic: more instrument reliably indicates more of what it measures, at least within some relevant range.

Compensation schedule i_h=ϕ(i_s) tells us how much happiness instrument is needed to offset or morally justify a given amount of suffering instrument.

Again, we can invoke the idealized hedonic egoist - the compensation schedule function as an indifference curve of this agent passing through neutral or absent experience.

Why instruments?

Trying to invoke “quantities” of happiness and suffering in the context of a discourse that references specific qualia or experiences, the abstract pre-moral “ground truth” intensity of those experiences, the abstract moral value of those experiences, and various discussion participants’ notions of or claims about the relationship between any of these concepts is extraordinarily conducive to miscommunication and lack of conceptual clarity even under the best of epistemic circumstances.23

More concretely, I have observed a natural and understandable failure mode in which one attempts to map “suffering” (as a quantitative variable) to something like “how much that suffering matters” (another quantitative variable). But such a relationship is, in the context of hedonic utilitarianism, some combination of trivial (because under hedonic utilitarianism, suffering and the moral value of suffering are intrinsically 1:1 if not conceptually identical) and confused.24

Instruments break this circularity by grounding discussion in concrete, in principle-measurable properties that virtually all people and conceptual frameworks can agree on. We define compensation through idealized indifference rather than positing mysterious common units. The moral magnitudes can remain ordinal within each channel; the compensation schedule provides the cross-calibration.

The compensation schedule’s structure

I claim that as i_s approaches some threshold from below, ϕ(is) grows without bound, reaching infinity at the threshold, creating an asymptote in the process. Beyond it, no finite happiness instrument can compensate.

Why this Is already radical

The radical implications (insofar as you think any of this is radical) aren’t at the threshold but in the approach to it. The compensation schedule growing without bound (i.e., asymptotically) means that some sub-threshold suffering would require 10^(10^10) happy lives to offset, or 1000^(1000^1000). Pick your favorite unfathomably large number - the real-valued asymptote passes that early on its way to infinity.

Once you accept that compensation can reach unfathomable heights while remaining not literally infinite, the step from there to “infinite” is small in an important sense. See the image above for a graphical comparison between this view and a naive, less plausible view in which there is a sudden discontinuous jump at the point of lexicality.

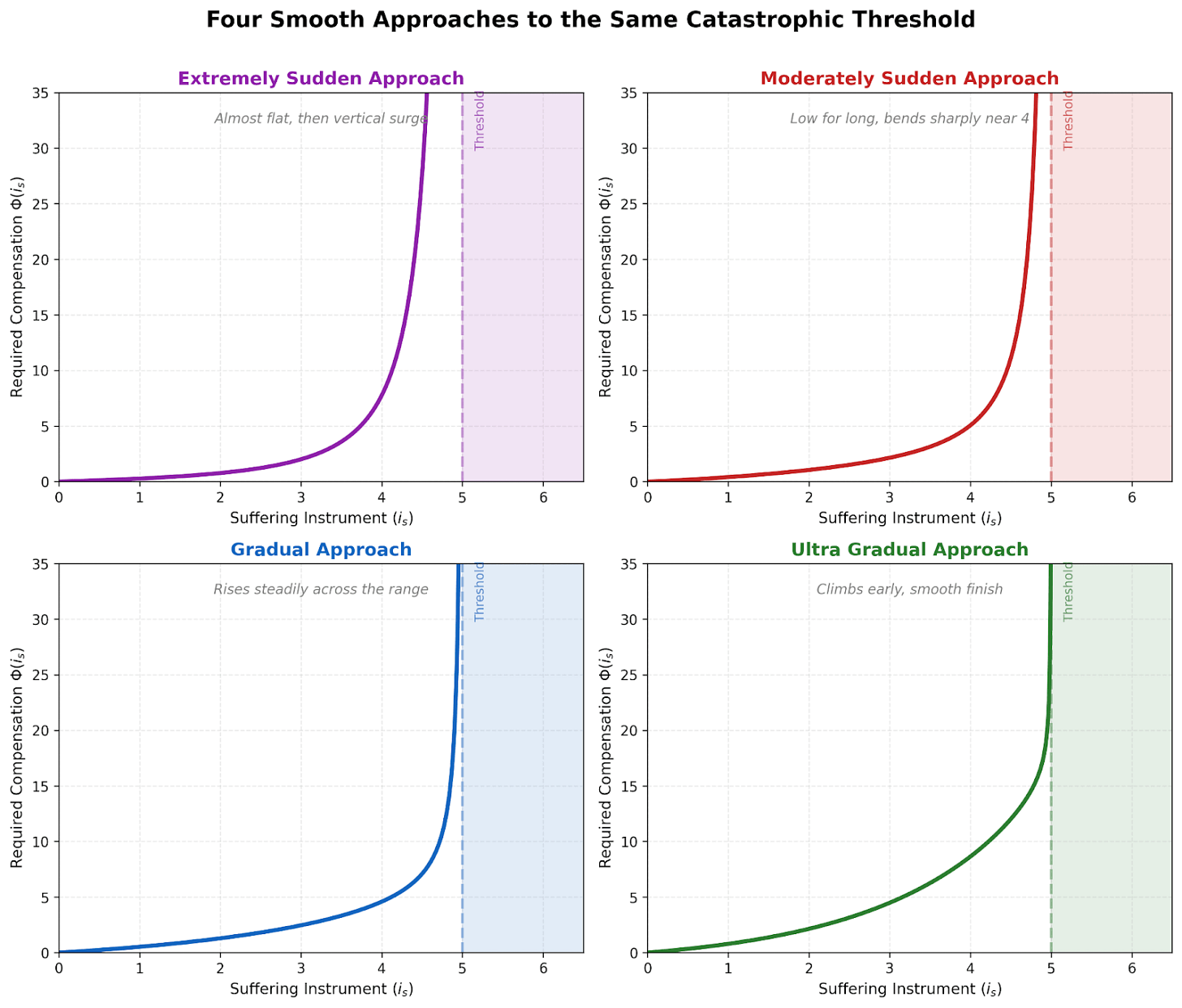

Note that my framework leaves quite a bit of room for internal specification. See the following graphic for representations of various models that all fit within the framework I’m arguing for. The actual, specific shape of the compensation curve and asymptote are hard but tractable questions for science and moral philosophy to make progress on.

8. Continuity and the location of the threshold

Critics object that lexical thresholds create arbitrary discontinuities where marginal changes flip the moral universe. This misunderstands the mathematical structure. As illustrated in the graphics above, the threshold is the limit point of a continuous process: as suffering intensity is approaches threshold is∗, the compensation function ϕ(i_s) approaches infinity. Working in the extended reals, this is left-continuous: lim[is→is*]ϕ(is)=∞+=ϕ(is*)

To be clear, whether we call this behavior ‘continuous’ depends on mathematical context and convention. In standard calculus, a function that approaches infinity exhibits an infinite discontinuity.25

I’m not arguing about which terminology is correct. The substantive point, which holds regardless of vocabulary, is that the transition to non-offsetability emerges naturally from an asymptotic process where compensation requirements grow without bound.

Where the threshold falls

The precise location of is∗ admittedly involves some arbitrariness. Why does the compensation function diverge at, say, the intensity of cluster headaches rather than slightly above or below?

This arbitrariness diminishes somewhat (though, again, not entirely) when viewed through the asymptotic structure. Once we accept that compensation requirements grow without bound as suffering intensifies, some threshold becomes inevitable. The asymptote must diverge somewhere; debates about exactly where are secondary to recognizing the underlying pattern.

9. From arbitrarily large to infinite: a small step

Many orthodox utilitarians accept that compensation requirements can grow without bound. They’ll grant that “for any amount of happiness M, no matter how large, there’s some conceivable form of suffering that would require more than M to offset.”

This is substantial common ground. We share the recognition that there’s no ceiling on how much compensation suffering might require. This unbounded growth has practical implications even before reaching any theoretical threshold.26

Once you’ve accepted that some suffering might require a number of flourishing lives that you could not write down, compute, or physically instantiate to morally justify, at least in principle, the additional step to “infinite” is smaller in some important conceptual sense than it might seem prima facie. The step to infinity requires accepting something qualitatively new but not especially radical.

This is not to say that all major disagreement is illusory.

Rather, my point here is that important questions and cruxes of substantial disagreement involves the actual moral value of various states of suffering, not the intellectually interesting but sometimes-inconsequential question of whether the required compensation is in-principle representable by an unfathomably large but finite number.

In other words, let us consider a specific, concrete case of extreme suffering: say a cluster headache lasting for one hour.

Here, the lexical suffering-oriented utilitarian who claims that this crosses the threshold of in-principle compensability has much more in common with the standard utilitarian who thinks that in principle creating such an event would be morally justified by TREE(3) flourishing human life-years than the latter utilitarian has with the standard utilitarian who claims that the required compensation is merely a single flourishing human life-month.

10. The phenomenology of extreme suffering

A fundamental epistemic asymmetry underlies this entire discussion: we typically theorize about extreme suffering from positions of relative comfort. This gap between our current experiential state and the phenomena we’re analyzing may systematically bias our understanding in ways directly relevant to the offsetability debate.

Both language and memory prove inadequate for conveying or preserving the qualitative character of intense suffering. Language functions through shared experiential reference points, but extreme suffering often lies outside common experience. Even those who have experienced severe pain typically cannot recreate its phenomenological character in memory; the actual quality fades, leaving only abstract knowledge that suffering occurred. When we model suffering as negative numbers in utility calculations, we are operating with fundamentally degraded data about what we’re actually modeling.

The testimony of those who have experienced extreme suffering deserves serious epistemic weight here. Cluster headache sufferers describe pain that drives them to self-harm or suicide for relief. To quote one patient at length:

It’s like somebody’s pushing a finger or a pencil into your eyeball, and not stopping, and they just keep pushing and pushing, because the pain’s centred in the eyeball, and nothing else has ever been that painful in my life. I mean I’ve had days when I’ve thought ‘If this doesn’t stop, I’m going to jump off the top floor of my building’, but I know that they’re going to end and I won’t get them again for three or five years27

Akathisia victims report states they judge “worse than hell,” driving some to suicide:

I am unable to rest or relax, drive, sleep normally, cook, watch movies, listen to music, do photography, work, or go to school. Every hour that I am awake is devoted to surviving the intense physical and mental torture. Akathisia causes horrific non-stop pain that feels like you are being continually doused with gasoline and lit on fire.28

The systematic inaccessibility of extreme suffering from positions of comfort is a profound methodological limitation that moral philosophy must recognize and mitigate with the evidential help of records or testimonies from those who have experienced the extremes.29

11. Addressing major objections

Let me address the most serious objections to the view that I have not already discussed. Some have clean responses while others reveal genuine uncertainties.

Time-granularity problem

Does even a second of extreme suffering pass the lexical threshold? A nanosecond? Far shorter still?

I began writing this post eager to bite the bullet, to insist that any time in a super-lexical state of extreme suffering, however brief, is non-offsetable.

But I am no longer confident; I don’t trust my intuitions either way, and I lack a strong sense of what an Idealized Hedonic Egoist would choose when faced with microseconds of otherwise catastrophic suffering.

To flesh out my uncertainty and some complicating dynamics a bit: it seems plausible to me that the physical states corresponding to intense suffering do not in fact cash out as the “steady state” intense suffering one would expect if that situation were to continue; that is, a nanosecond of placing one’s hand on the frying pan as a psychological and neurological matter isn’t in fact subjectively like an arbitrary nanosecond from within an hour of keeping one’s hand there. This may be a sort of distorting bias that complicates communication and conceptual clarity when thinking through short time durations.

On the other hand, at an intuitive level I can’t quite shake my sense that even controlling for “true intensity,” there is something about very short (subjective) durations that meaningfully bears on the moral value of a particular event.

Quite simply, this is an open question to me.

Extremely small probabilities of terrible outcomes

Does even a one in a million chance of extreme suffering pass the lexical threshold? One in a trillion? Far less likely than that?

I do bite the bullet on this one, and think that morally we ought to pursue any nonzero reduction of the probability of extreme, super-lexical suffering. Let me say more about why.

I’ve come to this view only after trying and failing to talk myself out of it (i.e., in the process of coming to the views presented in this post).

Under standard utilitarian theory, we can multiply both sides of any moral comparison by the same positive constant and preserve the moral relationship. This means that 10^(-10) chance of extreme torture for life plus one guaranteed blissful life is morally good if and only if one lifetime of extreme torture plus 10^10 blissful lives is morally good. I accept this “if and only if” statement as such.

Presented this way, the second formulation makes the moral horror explicit: we’re not just accepting risk but actively endorsing the creation of actual extreme torture as part of a positive package deal. And now we’re back to the same arguments for why extreme suffering does not become morally justifiable in exchange for any amount of wellbeing (the IHE and such).

I am happy to admit my slight discomfort - my brain, it seems, really wants to round astronomically unlikely probabilities to zero. But in a quite literal sense, small probabilities are not zero, and indeed correspond to actual, definite suffering under some theories of quantum mechanics and cosmology (i.e., Everettian multiverse, to the best of my lay-understanding).

Evolutionary explanations of intuitive asymmetry

The objection is some version of “Evolutionary fitness can be essentially entirely lost in seconds but gained only gradually; even sex doesn’t increase genetic fitness to nearly the same degree that being eaten alive decreases it. This offers an alternative, plausible alternative to “moral truth” as explanation for why we have the intuition that suffering is especially important.

I actually agree this has some evidential force, I just don’t think it is especially strong or overwhelming relative to other, contrary evidence that we have.

Evolution created many different intuitions, affective states, emotions, etc., that do not directly or intrinsically track deep truths about the universe but can, in combination with our general intelligence and reflective ability, serve as motivation for or be bootstrapped into learning genuine truths about the world.30

Perhaps most notably, some sort of moral or quasi-moral intuitions that may have tracked e.g., game theory dynamics and purely instrumental cooperation in the ancestral environment, but (at least if you’re not a nihilist) you probably think that these intuitions simply do happen to at least partially track a genuine feature of the world which we call morality.

Reflection, refinement, debate, and culture can serve to take intuitions given to us by the happenstance of evolution and ascertain whether they correspond to truth entirely, in part, or not at all.

For example, we might reflect on our kin-oriented intuitions and conclude that it is not in fact the case that strangers far away have less intrinsic moral worth. We might reflect on our intuition about caring for our friends and family and conclude that something like or in the direction of “caring” really does matter in a trans-intuitive sense.

This is, what I claim, we can and should do in the context of intuitions about the nature of hedonic experience. There’s no rule that evolution can’t accidentally stumble upon moral truth.

The phenomenological evidence, especially, remains almost untouched by this objection. When someone reports that no happiness would be worth the cluster headache they are having right now, that is a hypothesis whose truth value needn’t change according to how good pleasure can get.

“Doesn’t this endorse destroying the world?”

This common objection, often presented as a reductio, deserves careful response.

First, this isn’t unique to suffering-focused views. Traditional utilitarianism also endorses world-destruction when all alternatives are worse. If the future holds net negative utility, standard utilitarianism says ending it would be good.

Second, this isn’t strong evidence against the underlying truth of suffering-focused views. Consider scenarios where the only options are (1) a thousand people tortured forever with no positive wellbeing whatsoever or (2) painless annihilation of all sentience. Annihilation seems obviously preferable.

Third, the correct response isn’t rejecting suffering-focused views but recognizing moderating factors:

Moral uncertainty

I don’t have 100% confidence in any moral view. There might be deontological constraints or considerations I’m missing, and it’s worth making explicit that I’m not literally 100% certain in either thesis of this post.

Cooperation and moral trade

I, and other suffering-focused people I know, strongly value cooperation with other value systems, recognizing moral trade and compromise matter even when you think others are mistaken.

Virtual impossibility

This point, I think, is greatly underrated in the context of this objection and related discussions.

Actually destroying all sentience and preventing its re-emergence is essentially impossible with current or foreseeable technology. It is quite literally not an option that anyone has.

This point is suspiciously convenient, I recognize, but it also happens to be true.

Anti-natalism doesn’t actually result in human extinction except under the most absurd of assumptions.31 Killing all humans leaves wild animals. Killing all life on earth permits novel biogenesis and re-evolution. Destroying Earth doesn’t eliminate aliens. AI takeover scenarios involve a different, plausibly morally worse agent in control of the future and digital sentience.

At the risk of coming across as pompous, the suggestion that anything near my ethical views entails literal, real-life efforts to harm any human falls apart under even the mildest amount of serious and earnest scrutiny and, in my experience, seems almost entirely motivated by the desire to dismiss substantive and plausible ethical claims out-of-hand.

I want to be entirely intellectually honest here; I can imagine worlds in which a version of my view indeed suggest actions that would result in what most people would recognize as harm or destruction.

For instance, we can suppose that we had an extremely good understanding of physics and acausal coordination and trade across the Everettian multiverse and also some mechanism of precipitating a hypothetical universe-destroying phenomenon known as “vacuum collapse” and furthermore were quite sure that precipitating vacuum collapse reliably reduces the expected amount of non-offsetable suffering throughout the multiverse. At least a naive unilateralist’s understanding of my theory might indeed suggest that we should press the vacuum collapse button.

Fair enough; we can discuss this scenario just like we can discuss the possibility of standard utilitarianism confidently proclaiming that we ought to create a trillion near-eternal lives of unfathomable agony for enough mildly satisfied pigeons.

In both cases, though, moral discourse needs to recognize that as a matter of empirical fact there is actual no possibility of you or I or anyone doing either of these things in the immediate future. Neither theory is an infohazard, and both need to be discussed in earnest on the merits.

Irreversibility considerations

Irreversible actions that can be accomplished by a single entity or group warrant extra caution beyond simple expected value calculations. The permanence of annihilation requires a higher certainty bar than other interventions.

This is particularly important given the unilateralist’s curse: when multiple agents independently decide whether to take an irreversible action, the action becomes more likely to occur than is optimal. Even if nine out of ten careful reasoners correctly conclude that annihilation would be net negative, the single most optimistic agent determines the outcome if they can act unilaterally.

This systematic bias toward action becomes especially dangerous with permanent consequences. The appropriate response isn’t to abandon moral reasoning but to recognize that irreversible actions accessible to small groups require not just positive expected value by one’s own lights, but (1) robust consensus among thoughtful observers, (2) explicit coordination mechanisms that prevent unilateral action, and/or (3) confidence levels that account for the selection effect where one is likely the most optimistic evaluator among many.

General principle

Most fundamentally, it is better to pursue correct ethics, wherever that may lead, and then add extra-theoretical conservative, cooperation and consensus-based guardrails than to start with an absolute premise that one’s actual ethical theory simply cannot have counterintuitive implications.

12. Conclusion

Implications

Dozens, hundreds, or thousands of pages could be written about how the claims I’ve made in this post cash out in the real world, but to gesture at a few intuitive possibilities, I suspect that it implies allocating more resources to preventing and reducing extreme suffering, being more cautious about creating suffering-capable beings, and taking s-risks seriously. These are reasonable and, more importantly, plausibly true conclusions.

Indeed, more ought to be written on this, and I’d encourage my future self and others to do just this.

We keep what’s compelling

The view I’ve outlined is a refinement to orthodox total utilitarian thinking; we preserve what’s compelling while dropping an implausible commitment that was never required or, to my knowledge, explicitly justified.

The core insights of the Utilitarian Core remain intact:

Consequentialism: what matters is what happens.

Welfarism: the hedonic wellbeing of sentient beings is the sole source of intrinsic value.

Impartiality: welfare matters regardless of who experiences it.

Aggregation or summation: the moral value of the world is constituted by and equal to the collection of morally relevant states within it - regardless of which symbolic system best represents the actual nature of those states.

Maximization: more aggregate welfare is always better.

We drop what’s implausible

We abandon the assumption of universal offsetability, which was never a core commitment but rather a mathematical convenience mistaken for a moral principle.

Specifically, we drop the offsetability of extreme suffering; some experiences are so bad that no amount of happiness elsewhere can make them worthwhile. This isn’t because suffering and happiness are incomparable in principle, but because the nature of hedonic experience makes some tradeoffs categorically bad deals for the world as a whole.

Thank you to Max Alexander, Bruce Tsai, Liv Gorton, Rob Long, Vivian Rogers, and Drake Thomas for a ton of thoughtful and helpful feedback. Thanks as well to various LLMs for assistance with every step of this post, especially Claude Opus 4.1 and GPT-5.

Sometimes referred to as “lexicality” or “lexical priority.”

See later in this section for a more technical description of what exactly this means

In the standard story, so-called “utils” are scale-invariant, so we can set 1 equal to a bite of an apple or an amazing first date as long as everything else gets adjusted up or down in proportion.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy further subdivides these into what I will call the Extended [Utilitarian] Core:

“Consequentialism = whether an act is morally right depends only on consequences (as opposed to the circumstances or the intrinsic nature of the act or anything that happens before the act).

Actual Consequentialism = whether an act is morally right depends only on the actual consequences (as opposed to foreseen, foreseeable, intended, or likely consequences).

Direct Consequentialism = whether an act is morally right depends only on the consequences of that act itself (as opposed to the consequences of the agent’s motive, of a rule or practice that covers other acts of the same kind, and so on).

Evaluative Consequentialism = moral rightness depends only on the value of the consequences (as opposed to non-evaluative features of the consequences).

Hedonism = the value of the consequences depends only on the pleasures and pains in the consequences (as opposed to other supposed goods, such as freedom, knowledge, life, and so on).

Maximizing Consequentialism = moral rightness depends only on which consequences are best (as opposed to merely satisfactory or an improvement over the status quo).

Aggregative Consequentialism = which consequences are best is some function of the values of parts of those consequences (as opposed to rankings of whole worlds or sets of consequences).

Total Consequentialism = moral rightness depends only on the total net good in the consequences (as opposed to the average net good per person).

Universal Consequentialism = moral rightness depends on the consequences for all people or sentient beings (as opposed to only the individual agent, members of the individual’s society, present people, or any other limited group).

Equal Consideration = in determining moral rightness, benefits to one person matter just as much as similar benefits to any other person (as opposed to putting more weight on the worse or worst off).

Agent-neutrality = whether some consequences are better than others does not depend on whether the consequences are evaluated from the perspective of the agent (as opposed to an observer).”

For the remainder of this post, I’ll use and refer to the simpler five-premise Utilitarian Core rather than the eleven-premise Extended Core, though these are equivalent formulations at different levels of detail.

The Extended Core expands what is compressed in the five-premise version; “consequentialism” subdivides into commitments to actual consequences, direct evaluation, and evaluative assessment, “impartiality” into universal scope and equal consideration, and so on. Any argument that applies to one formulation applies to the other. Those who prefer the finer-grained taxonomy should feel free to mentally substitute it throughout.

Utilitarianism.net leaves out maximization; as of September 16, 2025, Wikipedia reads “Total utilitarianism is a method of applying utilitarianism to a group to work out what the best set of outcomes would be. It assumes that the target utility is the maximum utility across the population based on adding all the separate utilities of each individual together.”

By “summation” I mean a symmetric, monotone aggregation operator over persons or events. It need not be real-valued addition. But, conceptually, “addition” or “summation” does seem to be the right or at least best English term to use. The key point is that this operator needn’t be inherently restricted to the real numbers or behave precisely like real-valued addition.

See footnote above for elaboration and formalization.

Formal statement: A sufficient package for universal offsetability is an Archimedean ordered abelian group (V, ≤, +, 0) that represents welfare on a single scale. Archimedean means: for all a, b > 0 there exists n ∈ ℕ with n·a > b. Additive inverses mean: for every x ∈ V there is −x with x + (−x) = 0. Total order and monotonicity tie the order to addition. On such a structure, for any finite bad b < 0 and any finite good g > 0 there exists n with b + n·g ≥ 0. The Utilitarian Core does not by itself entail Archimedeanity, total comparability, or additive inverses. It is compatible with weaker aggregation, for example an ordered commutative monoid that is symmetric and monotone.

Proof that UC doesn’t entail offsetability by counterexample:

Represent a world by a pair (S, H), where:

S is a nonnegative integer counting catastrophic-suffering tokens,

H is any integer recording ordinary hedonic goods.

Aggregate by componentwise addition:

(S1, H1) ⊕ (S2, H2) = (S1 + S2, H1 + H2).

Order lexicographically:

(S1, H1) is morally better than (S2, H2) if either

a) S1 < S2, or

b) S1 = S2 and H1 > H2.

This structure is an ordered, commutative monoid. It is impartial and additive across individuals. Yet offsetability fails: if S increases by 1, no finite change in H can compensate.

“Tentatively” because I don’t have a rock-solid understanding or theory of either time or personhood/individuation of qualia/hedonic states.

Though I’m not familiar with current work in infinite ethics, my argument about representation choices seems relevant to that field. If your model implies punching someone is morally neutral in an infinite universe (because ∞ + 1 = ∞), don’t conclude ‘the math has spoken, punching is fine’; conclude you’re using the wrong math.

Words that start with A come before B, those with AA come before AB, and so on.

Here, higher dimensions are analogous to and representative of more highly prioritized kinds of welfare: perhaps the most severe conceivable kind of suffering, and then the category below that, and so on.

Other structures that avoid universal offsetability include ordinal numbers, surreal numbers, Laurent series, and the long line. The variety of alternatives underscores that real-number representation is a choice, not a logical necessity.

This analysis suggests utilitarianism might not entail the repugnant conclusion either. Just as some suffering might be lexically bad (non-offsetable by ordinary goods), perhaps some flourishing is lexically good (worth more than any amount of mild contentment). The five premises don’t rule this out.

However, positive lexicality doesn’t solve negative lexicality; even if divine bliss were worth more than any amount of ordinary happiness, it wouldn’t follow that it could offset eternal torture. The positive and negative sides might have independent lexical structures, a substantive claim about consciousness rather than a logical requirement.

I know this isn’t the technically correct use of “a priori.” I mean “after accepting UC but before investigating beyond that.”

Revised from the original agent-based economic formulation to fit the language of moral philosophy. Please see any mainstream economics textbook or lecture slides for the economic formulation with any amount of formalization or explanation. Wikipedia seems good as well!

I.e., state of the world A is better than B if and only if the expected value of A is greater than the expected value of B, where expected value is defined and determined by that function, u.

The explanation here is reasonably intuitive; essentially, the fact that all states of the world get assigned a real number means that enough good can surpass the value of any bad because there exists some positive real number n such that an-b > 0 for any positive real numbers a and b.

Rejecting premise 1, completeness is essentially a nonstarter in the context of morality, where the whole project is premised on figuring out which worlds, actions, beliefs, rules, etc., are better than or equivalent to others. You can deny this your heart of hearts - I won’t say that you literally cannot believe that two things are fundamentally incomparable - but I will say that the world never accommodates your sincerely held belief or conscientious objector petition when it confronts you with the choice to take option A, option B, or perhaps coin flip between them.

Rejecting premise 2, transitivity, gets you so-called “money-pumped.” That is, it implies that there are a series of trades you would take that leaves you, or the world in our case, worse off by your own lights at the end of the day.

Premise 4, independence, is a bit kinder to objectors, and I believe empirically observed insofar as it applies to consumer behavior in behavioral economics. But my sense is that it is very rarely if ever explicitly endorsed, and at least intuitively I see no case for rejecting it in the context of utilitarianism or morality more broadly. In the words of GPT-5 Thinking, “adding an ‘irrelevant background risk’ shouldn’t flip your ranking.”

I am using this term in a rather colloquial sense. Feel free to substitute in your preferred word; the description later in this paragraph is really what matters.

Wording tweaked in response to a good point from Toby Lightheart on Twitter, who (quite reasonably) proposed the term “pragmatically accept” with respect to the suffering itself. I maintain that we should note the “enthusiastic endorsement” of package deals that contain severe suffering.

I.e., earnest collaborative truth seeking, plenty of time and energy, etc.

For instance, one critic of lexicality argues that lexical views “result in it being ethically preferable to have a world with substantially more total suffering, because the suffering is of a less important type,” but this claim is circular; the whole debate concerns which kinds of worlds have “how much” suffering in the relevant sense, and in this post I am arguing that some kinds of worlds (namely, those that contain extreme suffering) have “more suffering” than other worlds (namely, those that do not).

In the extended reals with appropriate topology, such a function can be rigorously called left-continuous.

The asymptotic structure creates genuine practical constraints in our bounded universe. Feasible happiness is bounded - there are only so many neurons that can fire, years beings can live, resources we can marshal. Call this maximum H_max. When the compensation function Φ(i_s) exceeds H_max while still below the theoretical threshold, we reach suffering that cannot be offset in practice. At some level i_s_practical where Φ(i_s_practical) > H_max, offsetting becomes practically impossible even while remaining theoretically finite. This creates a zone of “effective non-offsetability” below the formal threshold.

Before taking this man’s revealed preference not to commit suicide as strong evidence against my thesis, I urge you to consider the selection effects associated with finding such quotes.

Cluster headaches and torture, yes, but also the heights of joy and subjective wellbeing.

Or at least influenced; we don’t need to get into the causal power of qualia and discussions in philosophy of mind here.

The practical implementation of anti-natalism faces insurmountable collective action problems that prevent it from achieving human extinction. Even if anti-natalists successfully refrain from reproduction, this merely ensures their values die out through cultural and genetic selection pressures while being replaced by those who reject anti-natalism. The marginal effect of anti-natalist practice runs counter to its purported goal: rather than reducing total population, it simply shifts demographic composition toward those who value reproduction.

Achieving actual extinction through anti-natalism would require near-universal adoption enforced by an extraordinarily competent global authoritarian regime capable of preventing any group from reproducing. Given human geographical distribution and the ease of small-group survival, even a single community of a thousand individuals escaping such control would be sufficient to repopulate. The scenario required for anti-natalism to achieve its ostensible goal is so implausible as to render it irrelevant to practical ethical consideration.

Nice post!

I really appreciate the vibe of valuing & listening to your internal disagreements w utilitarianism. I think people can get stuck in the framework & find it embarrassing to say “I don’t know how to articulate that this is wrong, but it’s wrong.” Formalizing those objections is also valuable, but I’m not sure I buy the incommensurability frame entirely.

In particular, it seems hard to know whether different types of suffering are incommensurable with each other, and if so which is the “highest order bit” we should care about. It does seem to me intuitively that at some level suffering is incomprehensibly, incommensurably bad — but I’m not sure I can pinpoint it. Your IHE thought experiment points towards one answer: can the suffering being survive psychologically intact enough that they can eventually recover? If they can’t, they can’t be compensated. (Though they could be pre-compensated I suppose…but maybe you could argue the post-suffering being is effectively a different one, one who didn’t come sent to the trade.)

I’m curious to turn over the distinction between accepting and creating suffering. I think from a standard act utilitarian frame there’s no difference — we’re just picking world A or world B. Potential objections imo are:

1) higher-order utilitarianism — you might suffer moral degeneration from making such choices, or be a worse/less-trusted collaborator. Or you just don’t trust yourself to make these kinds of choices, as a flawed human.

2) deontology — this is using people as ends.

3) preferences over histories. This is my pet objection to standard utilitarianism — it’s possible to formulate preferences over world histories, not just states. In this case: I’m just allowed to prefer not to create huge amounts of suffering.

Can I ask an ignorant question? Doesn't incommensurability violate impartiality, provided that all types of losses are not uniformly distributed across the population?

Here is my concern. If some harms are incommensurable (i.e., non-offsettable) and the risks or incidences of those harms are not evenly or uniformly distributed across persons, then a decision rule that lexically prioritises preventing such harms will, in practice, prioritise the interests of those who predominanlty are subject to such harms. That priority holds regardless of who they are, but because exposure is uneven, the rule systematically concentrates moral attention on a subset of persons. This yields de facto partiality, even if the rule is formally impartial (person-neutral in structure).