On suffering

Content warning: descriptions of very bad experiences. Not graphic but may be disturbing.

I

I am writing these words while sitting in a comfortable chair in a comfortable 70 degree house. And, I suspect, you are too. Basically comfortable, that is. Physically. Maybe you’re a little cold, but not consumed by the screaming anguish of an icy ocean you cannot escape. Maybe stressed, but not asphyxiating.

It’s times like these I find it far too easy to ignore the most urgent, most serious, most fundamental problem in our world.

II

Once in a while, most of us endure suffering that completely consumes us. This need not be as severe as the horrors your mind can conjure. A kidney stone. Childbirth. Stubbing your toe hard, even. Those first first few seconds, as your nerves radiate electric signals up your leg, through your spine and into your brain, there is nothing in the world but pain.

Talking—even thinking—about intense, acute suffering is not cool, fun, or sexy. We flinch away from it, in both memory and observational understanding. We understand tragedies through the number they kill, sidestepping the very process of death. We understand torture as a ‘human right abuse’ without staring directly in its face.

I was just watching “The Edge of Democracy” on Netflix, and the narrator mentioned that former president of Brazil Dilma Rousseff was tortured in 1970 by the Brazilian military. The documentary does not linger on this fact.

Sitting in a comfortable chair in a comfortable house, it is easy to mentally replace “tortured” with a more manageable word. “Imprisoned,” maybe, or even “beaten up.” Unjust imprisonment is an evil, but it is an evil I think I can grasp. I can imagine myself in prison and I can imagine the accompanying mental anguish, but I cannot imagine myself being tortured. Not really.

III

Language is, perhaps, humanity’s most powerful tool, but its power is limited. Words carry no intrinsic meaning; insofar as they evoke something visceral—a picture in your mind’s eye, say, or what feels like “intuitive understanding”—it is because they are a sign pointing to something you’ve experienced. More, our memories are notoriously unfaithful. Even what we think we remember is likely distorted or false.

This is why you and I can never know whether we experience the same color as we both point to a leaf and say “green.” It is also, I think, why the unthinkable urgency of intense suffering is so difficult to grasp, and so often eludes us entirely. No permutation of language can transmit the meaning of “suffering” itself; it is not a matter of finding the right words or the right author or poet. Without a landmark in one’s mind comprised of first-person experience, even the most elegant linguistic sign is left pointing toward a void.

And, while memory can assist us, it cannot complete the task. Think back to the last time you were consumed in pain. Can you summon the very essence of this experience, a visceral understanding of the sheer sensation? I suspect not. A crevasse stands between the experience itself and the mark it leaves on one’s mind.

An exception

I think there is one way in which we gain a more true understanding. During a time of suffering, this crevasse dissolves and our mental representation of the experience converges with the experience itself. It is then alone we might catch a glimpse of suffering’s otherwise-unthinkable urgency.

And yet this urgency prevents its very own recognition. When we ourselves undergo the worst, our minds and bodies scream in a deafening tone. We do not regard the urgency, the suffering itself, in abstract or conceptual terms. They are not things to be pondered; they are instead experienced directly without the mediating influence of words and symbols. During such times, empathy is not merely impossible but unthinkable. This is not a character flaw; even the most altruistic among us does not think of others while she is drowning.

Nonetheless, it is tragic.

During the rare occasion during which we viscerally understand intense suffering, it can be very challenging to take action to help others. And when, thank God, the agony subsides and our minds return from its all-consuming hell, again capable of empathy, the visceral sense of urgency has taken flight.

Looking back, it is difficult to summon conceptually what we went through but impossible to summon it emotionally. We rewrite our own history, recasting sheer suffering as “type 2 fun,” or “a learning experience,” or simply failing to remember it at all. Even if we manage to avoid these cognitive traps, the crevasse remains—an impassable gulf standing between us and a full appreciation of pain.

IV

Nonetheless, I think there is a window through which we can steal a glimpse. There are times of great pain that fall below the world-dissolving threshold I have described. Our minds remain, however burdened.

In Alaska

Five years ago, my Boy Scout troop went backpacking in Denali State Park (next to the national park). It remains the most “rugged” thing I’ve ever done, and it would have been a good experience if we had brought enough food.

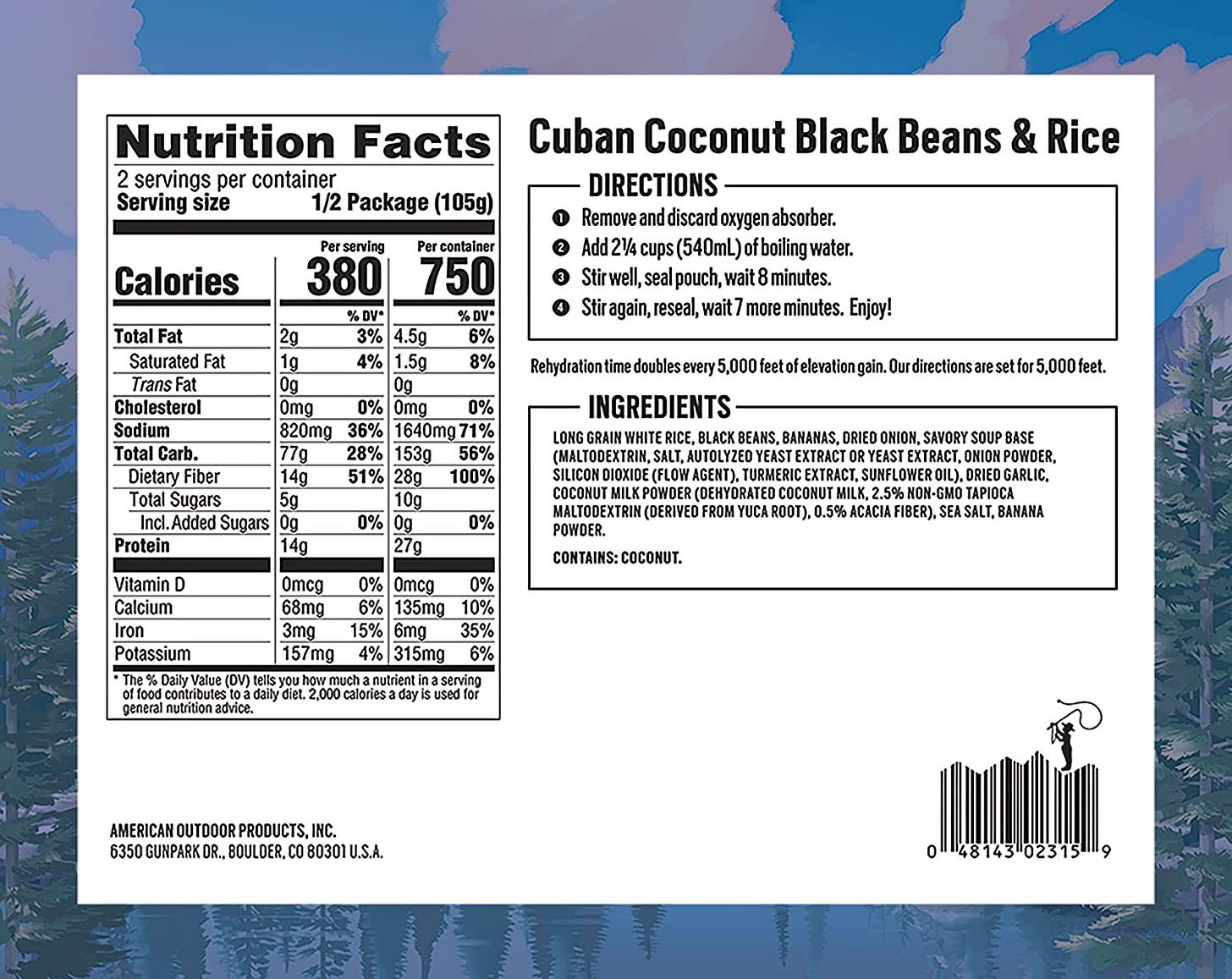

Long story short, the trip organizers mistakenly decided that “one serving” of a freeze-dried meal really meant one full meal. I don’t really know how this happened, since they were gracious and conscientious enough to procure me freeze-dried vegan backpacking food. Anyway, as you can see in the picture, 380 calories isn’t exactly a hearty dinner for a 16 year olds hauling his 30 pound backpack for miles on end.

Multiply that by ~3 and maybe throw in a Clif bar, and you’ve got something like 1300 calories a day, probably less than half of what we were burning. And inhaling some scrumptious carbs every few hours prevented us from reaching the energizing, hunger-neutralizing effects of uninterrupted ketosis.1

For much of human history, periods of famine were a regular occurrence. Even today, far too many people go hungry on a daily basis. I make no claim to have been placed in a uniquely bad situation. Its objective unremarkableness, however, does not negate how utterly terrible the hunger was. In hedonic terms, it was likely the single worst week of my life.

V The Window

My week in Alaska was the closest I have ever come to grasping the unthinkable urgency of hunger—not only for myself, but for the 690 million humans with access to fewer than 1800 calories per day and untold trillions of wild animals withering away under the silent brutality of nature. Comforted by my knowledge that the nutritional abundance of modernity lay just a few days in my future, that week was a mere shadow of the suffering that hunger can bring.

Sitting here, on a park bench in suburban Maryland, I cannot summon this sense of urgency that was directly manifest to me in the Alaskan backcountry. But for language’s fundamental inadequacies, it can indeed serve a profoundly important role; by encoding the raw experience of suffering into words and concepts—signposts and monuments to the memory they embody—one can retain a conceptual, abstract understanding of the suffering’s grave urgency in spite of that impassable emotional crevasse.

VII Conclusion

I’m not sure what I, or you, should do with this information. There is no cosmic justice in suffering on behalf of others, but there is something like cosmic justice in acting to prevent and ameliorate the worst experiences in our world.

Factory farming seems a reasonable place to begin, but wild animals plausibly suffer in far greater numbers. Veganism, though morally commendable, is not the sole means by which to help; very few among us, including those who eat meat, actively want animals to suffer. Perhaps we might reduce suffering the most by complementing the question of personal dietary consumption with a focus on preventing the maiming and castration of farm animals without anesthesia, among other interventions.

Among our own species, let us rectify the critical shortage of pain relief in low-income countries. And let us stare the very worst conditions right in their face, though merely as a first step to their mitigation. Cluster headaches, akathisia, and locked-in syndrome come to mind. I will not provide links; you may search for them if you wish. The elimination of these and similar conditions may be one of the most morally urgent issues that we face.

There is nothing beautiful or poetic about pain or agony. The world is not just. There is no virtue, no hidden meaning to be found. And I hope that my words might help to reduce the worst among it.

Thank you for reading.

Note: a previous version of this post appeared on the Effective Altruism Forum here.

Just five paragraphs above, I wrote the following:

Looking back, it is difficult to summon conceptually what we went through but impossible to summon it viscerally. We rewrite our own history, recasting sheer suffering as “type 2 fun,” or “a learning experience,” or simply do not remember it at all.

Despite my very own words, I utterly failed to do my memory justice. Instead, I slipped from a solemn and earnest meditation on suffering into the tone of a sardonic yet playful memoir. My words drip with contemptuous disregard for the memory they are supposed to represent, serving instead to entertain and cast myself as the type of person who can make jest of his own misfortune.

This shows, I think, the ease with which we misrepresent our past negative experiences, both to ourselves and to others.

You mention pain relief in low-income countries. And it does appear to be a direct and easy way to eliminate suffering, but it has a very interesting history. Have you ever read Dreamland by Sam Quinones? It's a history of the opioid crisis, and he lays some portion of the blame for it on precisely this sort of effort.

The book as a whole was largely concerned with the opioid epidemic in America, but part of the book had to do with the developing world, specifically Kenya. In 1980 Jan Stjernsward was made chief of the World Health Organization’s cancer program. As he approached this job he drew upon his time in Kenya years before being appointed to his new position. In particular he remembered the unnecessary pain experienced by people in Kenya who were dying of cancer. Pain that could have been completely alleviated by morphine. He was now in a position to do something about that, and, what’s more morphine is incredibly cheap, so there was no financial barrier. Accordingly, taking advantage of his role at the WHO he established some norms for treating dying cancer patients with opiates, particularly morphine. Essentially loosening the standards for their use. Then, to quote from the book:

"But then a strange thing happened. Use didn’t rise in the developing world, which might reasonably be viewed as the region in the most acute pain. Instead, the wealthiest countries, with 20 percent of the world’s population came to consume almost all–more than 90 percent–of the world’s morphine."

These standards and the broader ideology factored into pain being the fifth vital sign, and the development of oxycontin, and a bunch of other craziness like the idea that opioids weren't addictive as long as you were using them to treat actual pain. (For my money that last bit is the most fascinating bit of the whole story.)

In any case just about everything has weird second order effects. Including this.

But otherwise a great post!

Good post as always! I didn't have a term for Type II fun before but I'll keep that in mind from now on. Also, your Boy Scout troop sounds waaay more intense than mine was.