We Need a Netflix for News

Why the crisis in journalism is different and a new business model could help

Note: this post is speculative and I wouldn’t be surprised if there is some important factor that I’m neglecting.

1. Intro

One of the more concerning contemporary economic trends is journalism’s decline as an institution. This report by Brookings is a goldmine of evidence and analysis:

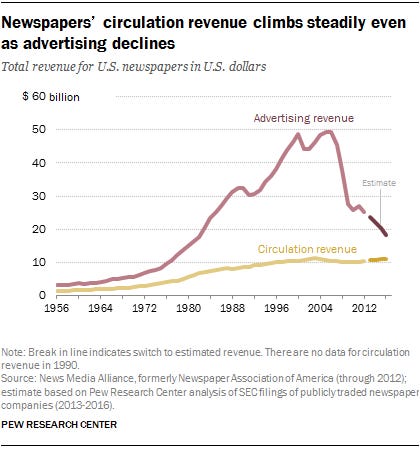

As you can see, the fall in newspaper ad revenue and circulation neatly coincides with the rise and proliferation of the internet. In case you’re thinking newspapers’ lost market share merely shifted to digital and cable news, not quite. According to Pew, “from 2008 to 2019, overall newsroom employment in the U.S. dropped by 23%.”

This trend has come down particularly hard on local newspapers and stations. In fact, just like the “opioid epidemic,” the “local news crisis” has practically become a proper noun.

2. This is different

Plenty of Disruption

Journalism is far from the only industry disrupted by the internet or by globalization before that. Probably every newspaper left standing has sent a reporter to some diner in Trump country to remind the urban elite that real people are hurt when the steel factory gets shipped overseas.

I think journalism’s struggle is fundamentally different, though. Without belittling the plight of who have lost their livelihoods to globalization, automation, or the internet, economists have a decent idea of how to mitigate this sort of damage. Namely, globalization and novel technologies make production more efficient and grow the economic pie. So, all we have to do is use some of this newfound wealth to compensate those harmed in the process.

Of course, a very legitimate criticism of neoclassical economics is that it affected economic liberalization much more than the creation of a robust social safety net. In other words, that theoretical Pareto improvement in which everyone is made better off never actually obtains. However, reforms like a universal basic income can, at least in principle, help the modern economy work for everyone.

Journalism

It seems to me, however, that journalism (or something equivalent) isn’t being made more efficient by the internet. Instead, the old regime of ad revenue-financed newspapers was a somewhat-strained but ultimately functional means of providing a public good. Namely, papers capitalized on an externality (consumers’ attention) generated by the provision of a public good (news, investigative journalism, holding public figures to account, creating common knowledge of current events).

Yes, people bought newspaper subscriptions, but ad revenue has always been greater than subscription revenue. From Pew:

This is not how things usually work. In general, public goods go unprovided without the government because individual consumers have an incentive to free-ride. In this case, though, it just so happened that a consumer trying to free ride (i.e. buying a subscription too cheap to finance the newsroom) gave his valuable attention to the paper, which it could then sell in the form of ad space - a serendipitous solution to what should have been a market failure.

Now that newspapers have to compete with the Internet for consumer attention, though, this solution is dissolving before our eyes. This is, remarkably, the economy getting less efficient thanks to technology and innovation. One insufficient but mitigating new solution is, for better or worse, that billionaires now own and personally finance institutions like the Washington Post.

3. A parallel universe

I can imagine an alternative universe in which there was a capital-c “Crisis” in TV and film. Suppose cable and cinemas never existed, and we went straight from 3 network channels to the internet. Before, these three channels produced all the movies and TV shows around. They had a near-monopoly on consumer attention and so could use their valuable ad sales to finance the production of amazing new content, which they did to compete with one-another and alternative sources of entertainment like books and board games.

At first, the legacy channels would probably do what so many news outlets are doing right now - that is, migrate online and put their content behind a paywall, or perhaps pump out the TV version of culture-war BuzzFeed-esque listicles in the hope of making content viral enough to pay for itself with ads.

Back to Earth

In real life, however, we don’t have a TV Crisis. We have Netflix, which not only aggregates existing TV shows and movies but generates its on high-quality content. There’s a reason virtually everyone I know, my family included, is willing to dish out $9-$18 each month for such a service; it provides immense consumer surplus.

How does it do that? By offering a huge assortment of movies and shows. Not all, to be sure, but enough that most people don’t feel the need to sign up for Hulu or Amazon Video as well. It would be as if “Newsflix” bought all the articles from the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and 40 smaller news outlets, in addition to launching their own for-profit ProPublica to make proprietary content.

While I won’t pretend to fully understand their business model, one fundamental principle working in Netflix’s favor is the economy of scale enabled by zero marginal cost distribution; if they spend $10 million to make a show, Netflix can sell the chance to watch it to anyone in the world for no additional cost.

So, why hasn’t a journalism version of Netflix been invented? Why can’t I pay someone $15 a month to have access to most of the great journalism out there? Why haven’t the benefits of zero marginal cost distribution been taken advantage of? I see three distinct but interrelated benefits from such a service, the last of which has two subparts:

Financing of journalism, a public good.

Elevated individual consumer surplus.

Diminished perverse incentives generated by the need for articles to maximize shares and views.

On the production side, content will be less clickbaity and generally higher quality.

On the consumption side, readers won’t have their attention itself monetized and manipulated a la endless scroll and algorithm-induced social media addiction.

4. Reasons why

As a starting point, we should expect markets to be efficient. A random blogger shouldn’t be able to identify a big, profitable business opportunity lying around for the taking. Some of the following problems are much more tractable than others.

1. Temporal relevance

Much more than TV shows or movies, news is mostly valuable for a limited amount of time after it is produced. Whereas I can get plenty out of watching a show or movie 5, 10, or 50 years after it was made, the same isn’t true for reporting. Perhaps if Netflix’s content became less entertaining after a few days or weeks, there would be no price at which the service could be profitable.

A silver lining, however, is that it might encourage the production of timeless, less “newsy”/horseracey journalism, which might be especially valuable. While news is a public good, I’m under no illusion that it is the best way of distributing information to the masses. Here is a “Case Against News” from professional contrarian Bryan Caplan.

2. Lack of coordination

Maybe the Times and Post would want to sell their content to an aggregator if it was already an industry norm, but Newsflix wouldn’t be able to pay the amount necessary for an institution to be the first mover. Much of the utility of Netflix comes from knowing that a large proportion of the quality content out there is available to subscribers. Likewise, maybe a Newsflix would need to have the NYT, Post, Wall Street Journal, Economist, and Bloomberg before consumers would find it worthwhile to buy a subscription.

Of course, this could be overcome with a huge amount of capital, both to incentivize the first few movers and to subsidize subscriptions for consumers

3. Ease of piracy

It’s not particularly difficult to pirate movies and shows, but it isn’t trivial either. Scraping text is (I assume) an order of magnitude easier. I can imagine that piracy would cut into a larger proportion of Newflix’s revenue than Netflix’s.

4. Newsroom resistance

We can treat newspapers like typical profit-maximizing firms staffed by Homo Economicus, but this obviously isn’t a perfect model. Journalists and editors likely often care a lot about their paper’s brand and independence, especially those with the most influence and experience. Maybe management would face resistance to selling their content.

On the other hand, journalists are surely keenly aware of the crisis facing their industry, and may be eager for their firm to find a more robust business model. I’m not sure in which direction staff influence would point.

5. Too small a market

Americans watch an astonishing amount of T.V., even after Netflix bit into cable’s market share:

Even if we took this study at its word and assumed 69% of Americans read the news (print or digital) in the last month, something tells me folks aren’t clocking more than a couple minutes of reading a day. So, it’s safe to assume that America as a whole will be less willing to pay for Newsflix than Netflix. This seems to me, unfortunately, the biggest barrier to such an aggregator’s profitability.

On the other hand, it’s not at all a lost cause. People were once willing to pay quite a bit for print content, even though it contained ads. It doesn’t seem crazy that consumers would be willing to buy a subscription if it gave them access to superior quality and variety relative to the free content out there.

Also, Substack itself is proof of concept (for more: the New Yorker) for subscription-based journalism! Check out the leaderboard:

Dozens of individual writers are making many thousands of dollars a month on this platform alone. While yours truly has yet to monetize his massive three person subscriber list, you can bet that before long you’ll see this blog on newsflix.com next to Yglesias’ and Greenwald’s.

5. Jeff Bezos, if you’re reading this:

Jeff Bezos has a net worth of about $182 billion and owns the Washington Post for (for which he paid $250 million). Amazon has a little experience trying moonshot business projects, and probably at least a few decent software engineers lying around. If he wanted to start Amazon News, he could. Yes, I find this unnerving as well, but it seems he hasn’t interfered with the Post’s operations or editorial decisions much.

Not only would such a service start out with one of the biggest names in journalism, but Bezos and Amazon could provide the capital and technical expertise to overcome any and all of the issues I mentioned.

6. Conclusion

Even if such a service were to work perfectly, there’s one issue that would remain unsolved: the local news crisis. Perhaps Newsflix would be willing to buy local outlets’ content, but it’s hard to imagine. After all, zero marginal cost distribution is the whole reason Newsflix seems plausible to me. While a subscriber in Berlin could read Springfield, IL’s local paper for no additional cost, this technical possibility is mostly irrelevant. So, I don’t see it making business sense for Newsflix to buy Springfield’s (or any other small city’s) content.

However, let not the perfect be the enemy of the good. Status quo journalism is unsustainable, and I want national outlets to be able to finance teams of investigative reporters to investigate anything they deem worth of investigation. I want politicians to know that their failures and successes alike will be reported to the world. I want editors and journalists to be able to focus on pumping out good and important content instead of competing for likes and shares in ruthless competition for ad revenue.

So, if you happen to know a billionaire, venture capitalist, or editor in chief willing to take on a new project, consider sending them this post.