Intro

There is no shortage of completely-justified anger at the U.S. criminal justice system. The list of grievances is long. Just off of the top of my head:

Excessive force by police, especially for black people.

Excessive enforcement of petty or victimless crimes, especially for black people.

Under-enforcement of serious crimes or insufficient protection of the community, especially for poor or black communities.

Under-enforcement of white-collar crime. Check out The Chickenshit Club.

Cash bail.

Discrimination in sentencing and prosecution.

Poor general conditions in prison.

Solitary confinement.

And this list took approximately zero time, cognitive effort, or research to generate. While the first two items have become particularly salient in the last few months and years, particularly following the killing of George Floyd, the other six and many more seem quite well-recognized, at least relative to other large social problems in America.

Some problems are clear

This is due to more than just the magnitude of these issues. Beyond that, they’re just so clear. For example…

Look into sentencing discrimination, and you’ll find dozens of papers on the topic in legal, political science, economic, and sociological journals. While there are, of course, obscure academic debates about whether things like race are directly, causally responsible for the observed discrepancies (as opposed to race being “merely” a proxy for a million other risk factors for incarceration), a cursory glance at Wikipedia tells you that sentencing disparities are not some urban legend.

You’ll find nuanced reports on the disparate impacts of the 1994 crime bill (think crack vs. powder cocaine) by liberal think tanks. Look at the “other side,” and you’ll find events with names like “Prison break: Why conservatives turned against mass incarceration.” Look some more, and you’ll find pages like this one with mountains of statistics on racial sentencing discrimination and enough footnotes to create a dissertation bibliography.

Even when these problems don’t emerge unambiguously from the data, they often feel intuitively, qualitatively real and wrong. No amount of data can say whether it is wrong that over 80,000 people are currently in solitary confinement in the U.S., but the sheer cruelty of the practice is impossible to overlook.

A natural comparison

The common theme is this: for many issues, including the eight on my list, there is a natural, intuitive “standard” or setpoint against which we can compare reality. For instance, most people probably think that in a just world, people convicted of the same crimes would tend to get the same sentences.

Likewise, it isn’t hard - in principle - to compare the reality of white collar crime prosecution to some ideal standard in which crimes are prosecuted in proportion to their degree of social importance rather the status of their perpetrator.

Of course, this comes in degrees. There is no distinct, obviously appropriate level for prison comfort and amenities, but we can be sure that it falls somewhere between “Auschwitz” and “five star hotel.”

Sentences are too long

Between different crimes, it seems clear that, all else equal, crimes that are more egregious or more indicative of a person’s future threat to others should carry longer sentences. Tell me that first degree murder should be met with a 30 year sentence, and I’ll tell you that bicycle thieves should face much less than that.

Let’s set aside questions of whether prison is an appropriate form of punishment or deterrence at all. When deciding an appropriate sentence for some person or crime, we’re likely to generate a number solely by comparing it to other crimes and sentences. For instance, five years might “sound right” for robbery if murder gets 30 years and cocaine sale gets two.

But, why have we decided that these lengths are even the right order of magnitude? Why does assault get you five years in prison instead of five months, five weeks, or five decades for that matter?

Sentences are too long

A longtime podcast addict, I recall listening to season 2 of the popular show Serial. I remember the host spending some time at a very typical courthouse in Cleveland and noting that cops, judges, and prosecutors all seemed to conceptualize the largely poor and black defendants as fundamentally different than them.

Maybe this sounds like woke or progressive nonsense, but I think it’s largely correct. To illustrate, consider the treatment of the dozens of very wealthy, mostly white parents (including some A- list celebrities) charged in the 2019 college admissions bribery scandal, who used their immense wealth to bribe their children’s way into elite colleges and very nearly succeeded. If any type of defendant was going to seem fully human but not particularly sympathetic, it would be them.

As described by Wikipedia and this recent Netflix documentary, those who pleaded guilty got anything from some community service and a (very affordable) fine to nine months in prison (the single longest sentence). Among those already sentenced, the median punishment seems to have been about two months locked up.

Now, compare this to that table of the median and mean prison sentences by crime category above. Seems awfully lenient, right? I too feel the retributive intuition that this type of white collar criminal should get a taste of what things are like for the disproportionately poor and black people convicted of shoplifting, drug possession, or assault, but that is taking things in the wrong direction!

We shouldn’t make rich white people’s sentences longer—we should use the treatment of rich white people as an improved (though by no means necessarily ideal) standard by which to sentence everyone.

Being an armchair psychologist

Clearly, prosecutors, judges, and the criminal justice system at large decided that ~2 months in jail was an appropriate degree of punishment and deterrence for this type of crime. Why was this the case? I’m sure there are many different explanations, but the completely unqualified armchair psychologist inside me imagines the following.

Like the admissions scandal defendants, Prosecutors and judges are by and large white and affluent. The former have a median salary of about $80,000, and virtually all prosecutors (I assume) earned a professional degree in law. More, both the judges and prosecutors involved in this case were almost certainly more experienced, better paid, and generally higher status than is typical.

A judge sentencing one of these defendants would have seen someone fundamentally similar to themselves—someone who also grew up in an affluent neighborhood, went to an elite college, and shares a broad set of professional class norms and values. And so this judge would have really, truly considered how bad it is to go to prison for two months. I imagine that the judge would have run a simulated of two months in prison for themselves, and concluded that this was the appropriate amount of “badness” as means of deterrence and retribution.

Normalize it.

This is a good thing! If this story is correct, it should be what happens during law creation, charging and sentencing all the time!

In case you don’t share this intuition, I encourage you to consider what you, yes you, would do to avoid going to prison for a week, or a month, or a year, or a decade. The police come tomorrow and take you away. Really, imagine it. Not just the literal time in prison, but also all the secondary social and professional effects as well.

Three Frameworks

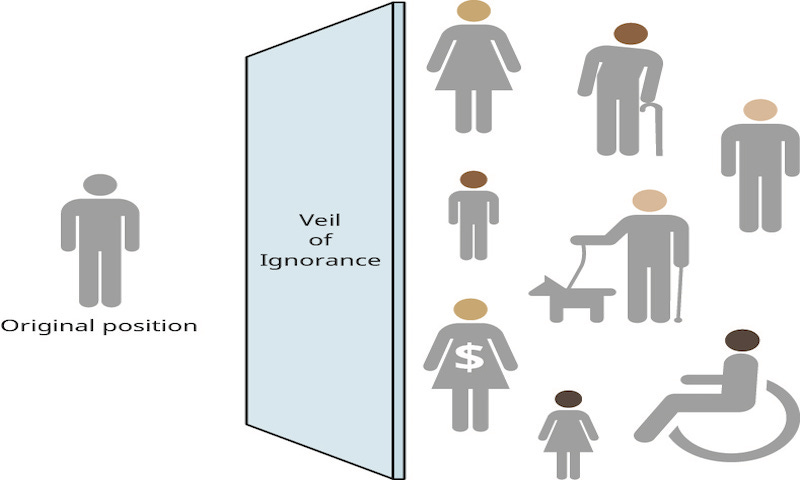

Consider Rawls’ “veil of ignorance.” What would crime sentences look like if created by someone who did not know which of the 300+ million Americans he or she would become?

In an economic framework, what is the point at which the marginal cost of an extra day in prison (as internalized by the prisoner, his family, his community, the taxpayers, etc.) matches its marginal benefit (through deterrence, preventing him from reoffending, and the psychological comfort offered to victims and other citizens)?

So, the three alternative frameworks for determining sentence length are

Rawlsian veil of ignorance

Economic marginal cost=marginal benefit analysis

Empathetic introspection, reflecting on what it really means to go to prison for a certain amount of time.

I suspect that all these frameworks would produce a set of quite similar sentences, and my central claim is that these sentences would almost universally be much, much shorter that they currently are.

Yes, there are a few crimes that might so strongly indicate that a person is likely to continue causing harm to others that a long prison sentence is warranted for the sole purpose of keeping him or her away from society. In the vast majority of cases, though, incarceration seems to be about deterrence and retribution, not direct crime prevention.

Look at that table of average sentence lengths again. For now, let’s exclude crimes like murder and rape that are so detested by our society that it may be difficult to empathize with the perpetrator. 26 months for burglary and drug trafficking, 2.5 years for assault, and nearly 5 for robbery?

I bet all three frameworks would generate something like three months for burglary and trafficking, six months for assault, and one year for robbery. Maybe more, but also maybe much less. The armchair psychologist inside me can only do so much.

A free lunch?

I was about to write one of those “there might be trade-offs but that’s ok” paragraphs, when I remembered a bit of contrarian counter-evidence. As it turns out, there is good evidence that deterrence depends vastly more on the likelihood of being caught for a crime than on sentence length once convicted.

Presumably there is some point at which sentences are so lenient that they stop deterring crime, but at the current margin it looks like near-universal sentence decreases could be a free (or steeply discounted) lunch for society!

In the end, whether you’re an ivory tower Rawlsian philosopher, neoclassical economic shill, or progressive bleeding heart empathizer, following one of these three frameworks would likely produce a much more humane society at strikingly low social cost.