Suffering-focused total utilitarianism

Total utilitarianism doesn't imply that suffering can be offset

Edit, Nov. 5, 2022: the original title and subtitle sucked so I changed them.

Context and intro

I developed the following beliefs and argument while taking part in Training for Good’s Red Team Challenge a few months back, the output of which was my team’s full piece Questioning the Value of Extinction Risk Reduction.

Under a form of utilitarianism that places happiness and suffering on the same moral axis and allows that the former can be traded off against the latter, one might nevertheless conclude that some instantiations of suffering cannot be offset or justified by even an arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

A case for “suffering-leaning ethics”

Introduction and motivation

To my understanding, “the expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive” means and can be rephrased as “all else equal, we should expect reducing the risk of human extinction to have morally good consequences, whatever those might be.” Of course, “whatever those might be” leaves much to be desired. I am taking as given that consequences are morally relevant if and only if they matter for the wellbeing of sentient entities; I expect few, if any, self-described consequentialist effective altruists will object.

More contentiously, the following argument is phrased in terms of and therefore implicitly takes hedonic utilitarianism as given. That is, I assume that pleasure is the sole moral good and suffering the sole bad, though I often substitute “happiness” for “pleasure” because of its broader and more neutral connotation.

That said, I am very confident (95%) that the argument is robust to different understanding of “wellbeing” represented in the EA community, such as a belief in the goodness of non-hedonic “flourishing” or life satisfaction as distinct from hedonic pleasure. Negative utilitarians, who believe it is never morally acceptable to increase the total amount of suffering, may agree with some of my reasoning but are unlikely to find the argument compelling at large.

Why I do not find one argument for the in-principle moral “justifiability” of any amount of suffering convincing

In Defending One-Dimensional Ethics, Holden Karnofsky argues that “for a low enough probability, it’s worth a risk of something arbitrarily horrible for a modest benefit.” Under standard utilitarian assumptions, we can multiply each side of this “equation” quoted above by a large number1 and derive the corollary that a world with arbitrarily high disvalue (suffering) can be made net-positive with some arbitrarily high amount of value (happiness).

Upon first reading Karnofsky’s post, I acknowledged (grudgingly) that the argument was sound. My limited biological brain with its evolution-borne intuitions just wasn’t up to the task of reasoning about unfathomably-large hedonic quantities, I assumed, and a wiser, more rational being would see that the claim in bold above is true.

I’ve since changed my mind and this post explains why. More precisely, I will argue for the following thesis:

Under a form of utilitarianism that places happiness and suffering on the same moral axis and allows that the former can be traded off against the latter, one might nevertheless conclude that some instantiations2 of suffering cannot be offset or justified by even an arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

Defending this thesis and critiquing the previous claim

As a simple matter of preference, it seems that humans are generally3 willing to trade some amount of pain for some ‘larger’ amount of pleasure, all else equal.4[4] Nonetheless, there are some amounts of suffering that I would not accept in exchange for any amount of happiness, and, I believe, many besides me share this preference. In one sense, such preferences are just that – preferences, or descriptions of how a person behaves or expects they would behave in the relevant circumstances.

For myself and I believe many others, though, I think these “preferences” are in another sense a stronger claim about the hypothetical preferences of some idealized, maximally rational self-interested agent. This hypothetical being’s sole goal is to maximize the moral value corresponding to his own valence. He has perfect knowledge of his own experience and suffers from no cognitive biases. You can’t give him a drug to make him “want” to be tortured, and he must contend with no pesky vestigial evolutionary instincts.

Those us who endorse this stronger claim will find that, by construction, this agent’s preferences are identical to at least one of the following (depending on your metaethics):

One’s own preferences or idealized preferences

What is morally good, all else equal

For instance, if I declare that “I’d like to jump into the cold lake in order to swim with my friends,” I am claiming that this hypothetical agent would make the same choice. And when I say that there is no amount of happiness you could offer me in exchange for a week of torture, I am likewise claiming this agent would agree with me.

To be clear, I am arguing neither that my expression of such a preference makes it such that the agent would agree, nor that his preference is defined as my own, nor that my preference is defined as his.

Rather, there are at least two ways my preference and this agent’s might diverge. First, I might not endorse my de facto preference as the egotistically rational thing to do. For instance, I could refuse to jump in the lake in spite of my own higher-order belief that it is in my own hedonic interest to. Second, I might be mistaken about what this agent’s choice would be. For instance, perhaps the lake is so cold that the pain of jumping in is of greater moral importance than any happiness I obtain.

To reiterate, I, and I strongly suspect many others, believe that this egoistic being would indeed refuse a week of hideous torture even in exchange for an arbitrarily large hedonic reward, which might even last far longer than a human lifespan.

Formal Argument

We can formalize the argument I’ve been developing as follows:5

(Premise) One of the following three things is true:

One would not accept a week of the worst torture conceptually possible in exchange for an arbitrarily large amount of happiness for an arbitrarily long time.6

One would not accept such a trade, but believes that a perfectly rational, self-interested hedonist would accept it; further this belief is predicated on the existence of compelling arguments in favor of the following:

Proposition (i): any finite amount of harm can be “offset” or morally justified by some arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

One would accept such a trade, and further this belief is predicated on the existence of compelling arguments in favor of proposition (i).

(Premise) In the absence of compelling arguments for proposition (i), one should defer to one’s intuition that some large amounts of harm cannot be morally justified.

(Premise) There exist no compelling arguments for proposition (i).

(Conclusion) Therefore, one should believe that some large amounts of harm cannot be ethically outweighed by any amount of happiness.

Defending Premise 3

Here, I will present evidence that there exists no compelling argument that any finite harm can in principle be justified by a large enough benefit (i.e., proposition (i)). Of course, this evidence is inherently inconclusive, as it isn’t possible to show that something doesn’t exist. I encourage readers to link or describe proposed counterexamples in the comments. Nonetheless, I will argue that one popular argument which seems to show proposition (i) to be true is fundamentally flawed.

Karnofsky’s post Defending One-Dimensional Ethics is the most complete, layperson-accessible defense of such a position that I am aware of. It is also particularly conducive to my critique because of his conclusion that “for a low enough probability, it’s worth a risk of something arbitrarily horrible for a modest benefit,” which seems ethically equivalent to the claim that “for a large enough benefit, it’s worth something arbitrarily horrible.” Karnofsky’s argument consists of a series of compelling premises and subsequent intermediate steps–each of which seems intuitively correct, logically sound, and morally correct on its own–leading to this non-obvious conclusion.

Fundamentally, however, the post errs by employing the example of “a 1 in 100 million chance of [a person] dying senselessly in [the] prime of their life” as an accurate, appropriate illustrative example of the more general “extremely small risk of a very large, tragic cost.” On the contrary, an unwanted death seems to me (1) the removal of something good rather than the instantiation of suffering7 and (2) qualitatively less severe (and quantitatively smaller in magnitude, if you prefer) than other conceivable examples of a “large, tragic cost.”

To his credit, Karnofsky anticipates this second objection and includes a brief consideration and rebuttal in his dialogue:

[Utilitarian Holden]

...for a low enough probability, it’s worth a risk of something arbitrarily horrible for a modest benefit.

[non-Utilitarian Holden]

Arbitrarily horrible? What about being tortured to death?

[Utilitarian Holden]

I mean, you could get kidnapped off the street and tortured to death, and there are lots of things to reduce the risk of that that you could do and are probably not doing. So: no matter how bad something is, I think you’d correctly take some small (not even astronomically small) risk of it for some modest benefit. And that, plus the "win-win" principle, leads to the point I’ve been arguing.

On the object level, it seems plausible to me that there might be no action that those like myself and some readers, fortunate to live in safe geographical area during the safest part of human history, could take to (prospectively) reduce the risk of being tortured to death, because the baseline probability is so low. Further, an altruist might rationally accept some personal risk in exchange for reducing the risk of this outcome to others.

But this all seems beside the point, because we humans are biological creatures forged by evolution who are demonstrably poor at reasoning about astronomically good or bad outcomes and very small probabilities. Even if we stipulate that, say, walking to the grocery store increases ones’ risk of being tortured and there exists a viable alternative, the fact that a person chooses to make this excursion seems like only very weak evidence that such a choice is rational.

I concede that (under the above stipulations) the conclusion “a rational hedonist would never walk to the store” seems counterintuitive, but it does not seem to me any more counterintuitive than some of the implications of a truly impartial total utilitarianism (which largely run through strong longtermism). In the post, Karnofsky convincingly shows that a small benefit to sufficiently many people may justify a small risk of death. In fact, I even think a (different) modified version of the argument convincingly shows the same to be true for a more tolerable amount of suffering.

But, as far as we know, there’s no law written in the fabric of the universe or in the annals of The Philosophical Review stating that an arbitrarily small probability of terrible suffering is morally equivalent to a more certain amount of a lesser evil, or that the torture of one is ethically interchangeable with papercuts for a trillion.

Affirmative argument against proposition (i)

To rephrase that more technically, the moral value of hedonic states may not be well-modeled by the finite real numbers, which many utilitarians seem to implicitly take as inherently or obviously true. In other words, that is, we have no affirmative reason to believe that every conceivable amount of suffering or pleasure is ethically congruent to some real finite number, such as -2 for a papercut or -2B for a week of torture.

While two states of the world must be ordinally comparable, and thus representable by a utility function, to the best of my knowledge there is no logical or mathematical argument that “units” of utility exist in some meaningful way and thus imply that the ordinal utility function representing total hedonic utilitarianism is just a mathematical rephrasing of cardinal, finite “amounts” of utility.

Absence of evidence may be evidence of absence in this case, but it certainly isn’t proof. Perhaps hedonic states really are cardinally representable, with each state of the world being placed somewhere on the number line of units of moral value; I wouldn’t be shocked. But if God descends tomorrow to reveal that it is, we would all be learning something new.

While far from necessary for my argument, it may be worth noting that an ethical system unconstrained by the grade-school number line may still correspond, rigorously and accurately, to some other mathematical model.

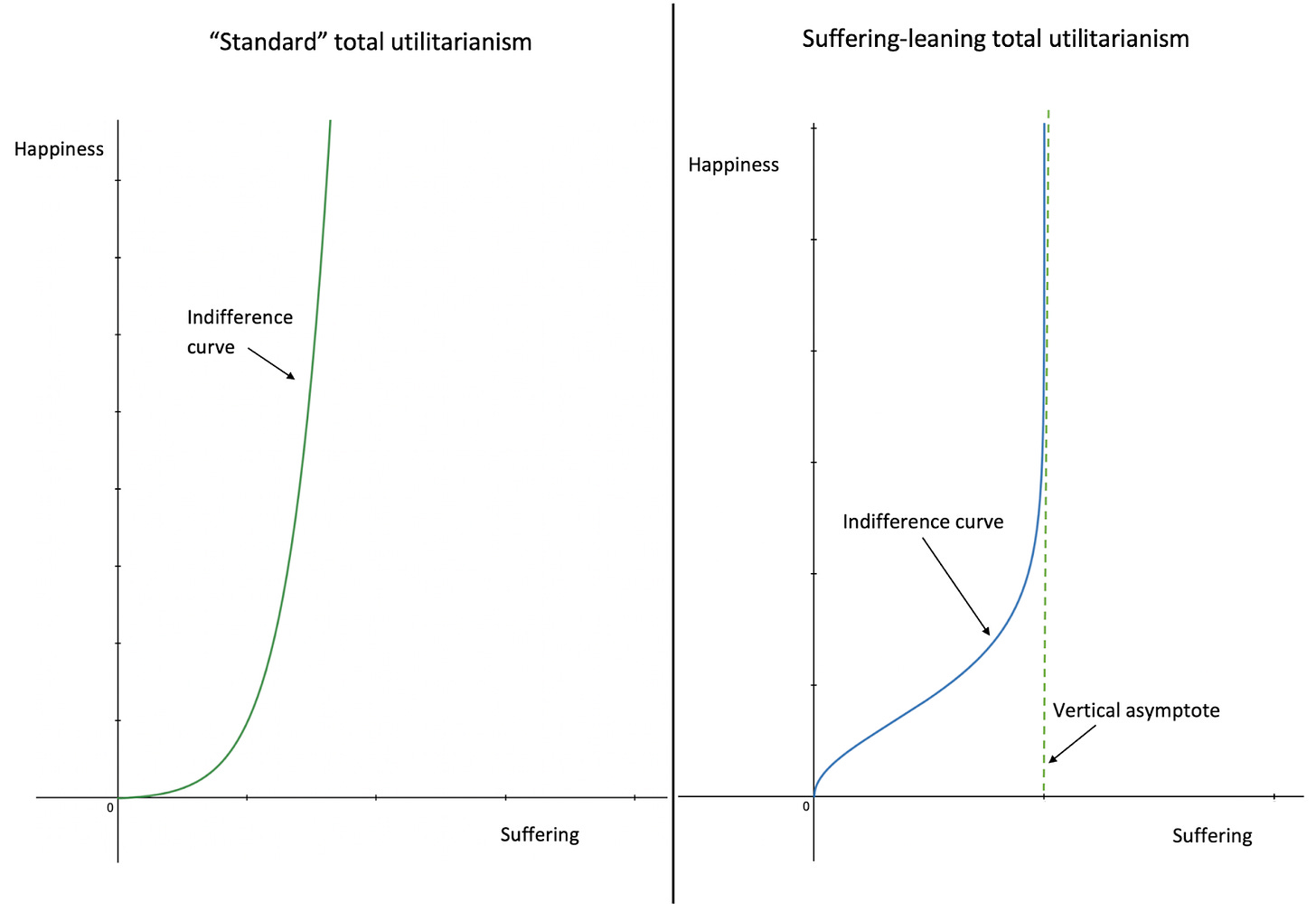

One such relatively simple example might be a function mapping some amount of suffering (which we can plot on the x-axis of a simple cartesian plane) to an amount of happiness whose moral value is of the same magnitude (on the y axis); that is, the “indifference curve” of a self-interested rational hedonist. Though “default” total utilitarian views seem to imply that such a function’s domain must be the entire set of non-negative real numbers, it is easy enough to construct a function with a vertical asymptote instead.8

The place of ethics in our argument

Assigning (some amounts) of suffering greater ethical value does not necessarily make human extinction more preferable. One might believe, for instance, that humanity will alleviate suffering throughout the rest of the universe, should it continue to survive.9

However, enabling such “cosmic rescue missions” hardly seem the motivation for or reasoning behind longtermism-motivated extinction reduction projects. We should be skeptical, indeed, that spreading humanity or post-humanity throughout the universe would lead to a reduction in the amount of “unjustifiable” (in the sense I’ve been describing) suffering.

If this is so, it could render actions to reduce the risk of human extinction per se morally indefensible. And if humans’ continued existence really can be expected to alleviate such large amounts of suffering, this should be affirmatively made.

Final notes

Over the course of this project, I gradually came to believe (~85%) that the question of the value of ERR, which more literalist readers (like myself) might take to mean

Should we turn down the magic dial which controls the probability that all humans drop dead tomorrow?"

is not merely different from but in practice essentially unrelated to the more action-relevant question of

Given the world we live in, should act to reduce the likelihood that there are no humans or post-humans alive in, say, 10,000 years (or virtually any other time frame)?

This is true for what seem like pretty contingent reasons. Namely, most of the risk of human extinction runs through

Unaligned AI, which can be thought of as an agent in its own right and a net-negative one at that, and

Biological pathogens, against which (it seems to me, though I am uncertain) most interventions aimed at preventing extinction per se would also (and plausibly to an even greater degree) prevent societal breakdown, conflict, and impaired coordination.

That said, there are of course "all or nothing" sources of extinction risk - such as large asteroid impact or "stellar explosions" - that more closely resemble the "all humans drop dead tomorrow" scenario from above.10 And, indeed, reducing the risk of these catastrophes seems essentially equivalent to reducing the risk of extinction "all else equal."

Naively take my probabilities I offered above (30% that ERR is good all else equal in theory, 75% that it is good in practice) and (conveniently) assume away any correlation, we get a 52.5% chance that acting to prevent these "all or nothing" extinction events is bad, but acting to prevent misaligned AI and (less certainly, and probably to a lesser extent), biorisk is good.

Fortunately, accepting this conclusion doesn't seem to imply much change to the actions of the longtermist community in mid-2022.

But that could change if, say, we discover how to create AGI in such a way that it no longer threatens to cause suffering or harm other beings in the universes but nonetheless remains an extinction threat. Less speculatively, this very tentative conclusion suggest that any peripheral efforts to, for instance, prevent a supervolcano eruption may be a poor use of resources if not actively harmful.

Finally, I'd highlight two research programs that seem to me very important:

Unpacking which particular biorisk prevention activities seem robust to a set of plausible empirical and ethical assumptions and which do not; and

Seeking to identify any AI alignment research programs that would reduce s-risks by a greater magnitude than "mainstream" x-risk-oriented alignment research.

More specifically, the quantity 1/p if p refers to the probability of the terrible event.

I am intentionally avoiding words like “amount” or “quantity” here

Or would be, given the opportunity.

I considered supporting this claim with empirical psychological or economic literature. However, a few factors contributed to my decision not to:

The failure of many papers in the relevant subfields to replicate;

The author’s and a reviewer’s intuitions that the claim is very likely to be correct and unlikely to be challenged; and

An abundance of simple, common sense examples, such as humans’ general willingness to:

Wait in line for something we want

Take foul-tasting medications

Study for tests

Eat spicy food

This can be modeled as follows, where:

P≔ an ideally rational egoistic hedonist would not accept the trade described.

I≔ Proposition (i): any finite amount of harm can be “offset” or morally justified by some arbitrarily large amount of wellbeing.

C≔ there exists a compelling argument for proposition (i).

Even if this entails setting aside speculative empirical constraints such as the amount of energy in the universe).

One might reasonably object that there is no fundamental moral or ontological difference between the removal of a good and creation of a bad. I believe, however, that the second consideration (if one accepts it) suffices to show that a single unwanted death is at least plausibly too small in magnitude to serve as a general example of a “very large and tragic cost.”

Because there are no well-defined “units” of happiness and suffering, the curve on the left (which increases in slope with suffering) could instead be shown as a straight line of constant slope. The key distinction is that the right curve alone has a vertical asymptote.

As shown in the middle bolded column of the table below, moving towards suffering focused ethics should lead one to believe that reducing extinction is better than previously thought in scenarios 1 and 3, and worse in 2 and 4. The final, rightmost column presents term a term (p_1s_1+p_3s_3)−(p_2s_2+p_4s_4) whose sign specifies whether the argument makes the value of preventing extinction better (if positive) or worse (if negative), relative to a less suffering-focused perspective.

In aggregate, this term (p_1s_1+p_3s_3)−(p_2s_2+p_4s_4) can be understood as the expected effect of human extinction on unjustifiable suffering, setting aside any impact on wellbeing.

One unifying characteristic of these might be "physical destruction of a significant portion of Earth."

Aaron and I have already conversed on the subject, but for those interested, I wrote a reply, in which I destroyed Aaron with facts and logic :).

https://benthams.substack.com/p/contra-bergman-on-suffering-focused